Iran’s Foreign Policy Crisis: Trapped with No Friends?

Iran is often seen as a rogue state that defies international norms and threatens regional stability. But this image is too simplistic and misleading. Iran’s foreign policy is complex and nuanced, influenced by many factors and actors, both internal and external.

In this post, I want to examine Iran’s current foreign policy challenges and opportunities, focusing on its relations with the three Great Powers: Russia, China, and the US.

I will argue that Iran faces a foreign policy deadlock, as it seeks more respect and reciprocity from Russia, China, the US. But it faces resistance from hardliners within its own political system, who oppose any compromise or concession on Iran’s nuclear program or regional role, and a US that appears locked into permanent hostility with Iran.

Iran’s Foreign Policy Factors and Actors

Iran’s foreign policy is shaped by a variety of factors, such as its history, ideology, geography, economy, and politics. Iran has a long and proud history of civilization and culture, but also a history of foreign intervention and domination.

The Iranian government’s ideology is based on the Islamic Revolution of 1979, which overthrew the US-backed monarchy and established a theocratic republic. Iran’s geography is strategic but also challenging, as it borders seven countries and three seas. Iran’s economy is dependent on oil exports but also suffers from sanctions and mismanagement. Iran’s politics is complex and dynamic, as it involves different institutions and factions that have different interests and agendas.

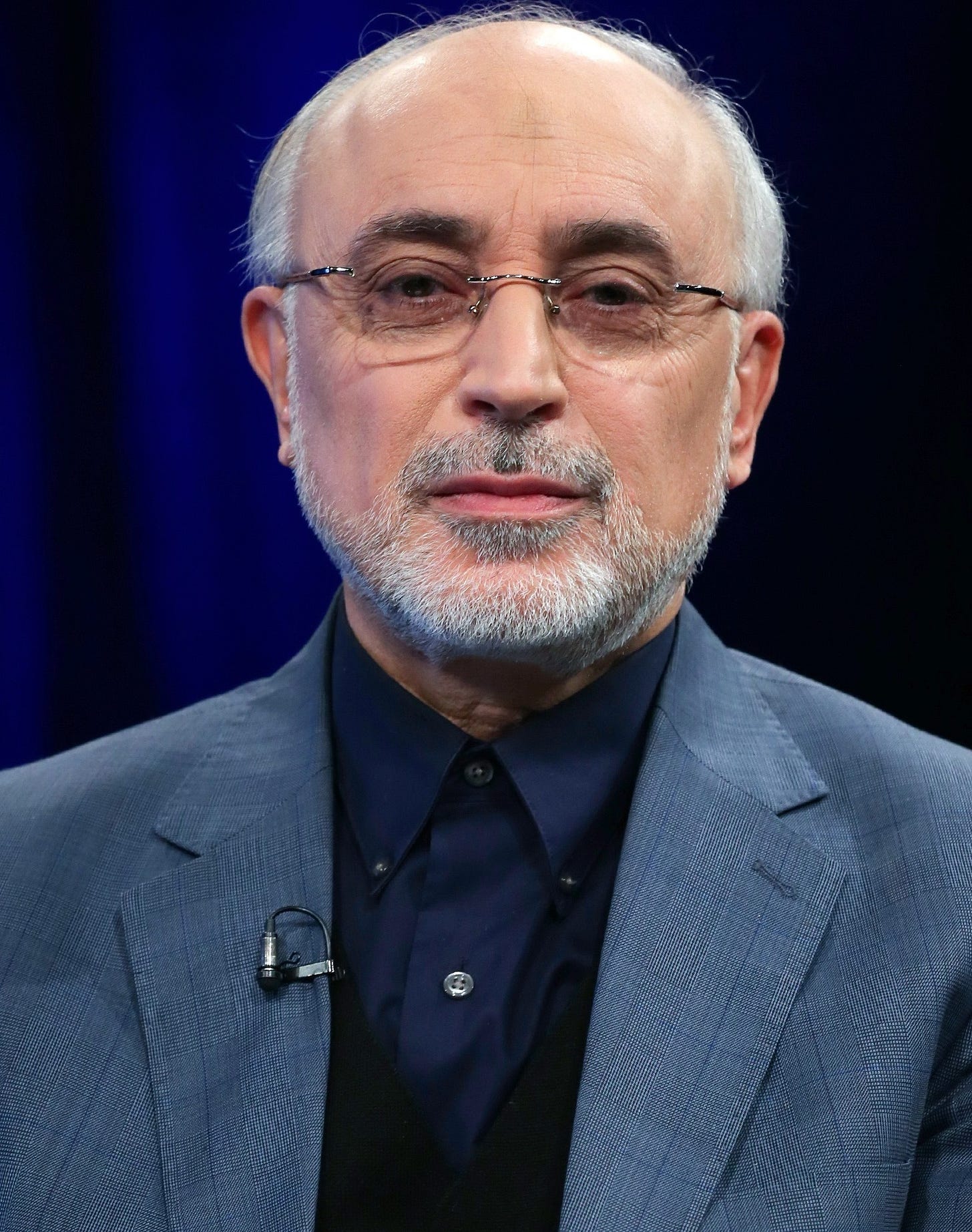

These internal divisions among Iran’s political elite over foreign policy have been evident recently in an interview with Ali Akbar Salehi. Salehi is a physicist, veteran diplomat and nuclear negotiator, who has held key positions in both the Ahmadinejad and Rouhani administrations. Salehi belongs to a faction that is increasingly called the “third way” in Iranian politics. This faction does not want to pursue rapprochement with the US and its allies, as some hardliners accuse moderates like Rouhani and Zarif of doing.

Ali Akbar Salehi, former Iranian Foreign Minister (2011-13) and head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (2013-21)

But it also does not want to isolate Iran from the rest of the world, as some hardliners do. Instead, this faction, which includes influential figures from across the political spectrum, such as Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, the current Speaker of the Parliament, Ali Larijani, the former Speaker of the Parliament and current Member of Expediency Discernment Council, and Kamal Kharazi, the former Foreign Minister and current Head of Strategic Council on Foreign Relations, seeks a more balanced and pragmatic foreign policy. One that does not depend too much on either the so-called “East or West.”

There are signs that the conservative Raisi administration, and incumbent foreign minister Hossein Amir Abdollahian, largely share this faction’s views. They have framed their foreign policy agenda as one of seeking balance. And they have tried to improve ties with regional rivals, such as Saudi Arabia, and join multilateral platforms, such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), to boost Iran’s regional and international status and leverage.

Raisi has also continued indirect negotiations with the US, though not through a framing of pursuing closer ties with the west, like Rouhani and Zarif did, but as a way of lifting sanctions and easing economic pressure.

But this third way faction faces resistance from hardliners on their right, who still wield power and influence within Raisi’s administration. They reject any negotiation with the US as what they call “pure damage.” They point to history, such as how Iran’s cooperation with the US in Afghanistan after 9/11 was rewarded with being labeled as part of the Axis of Evil, and how the US withdrew from the JCPOA despite Iran’s compliance. They also invoke ideology, such as the Islamic Republic’s founding principles of resistance and independence from foreign interference. They oppose any compromise or concession on Iran’s nuclear program or regional role and call for a self-reliant and self-sufficient economy that can endure sanctions. This faction sees dialogue with the US as a trap and a threat, rather than an opportunity and a benefit.

Iranian Anger with Russia and China

Iran has relied heavily on Russia and China for economic, political, and military support in recent years, especially after the US withdrew from the JCPOA in 2018 and reimposed sanctions on Iran. Iran has also backed Russia militarily in its conflict with Ukraine, despite facing immense backlash from Europe. However, Iran’s over-reliance on Russia and China has also exposed its vulnerabilities and limitations, as Russia and China pursue their own interests in the region, often at Iran’s expense.

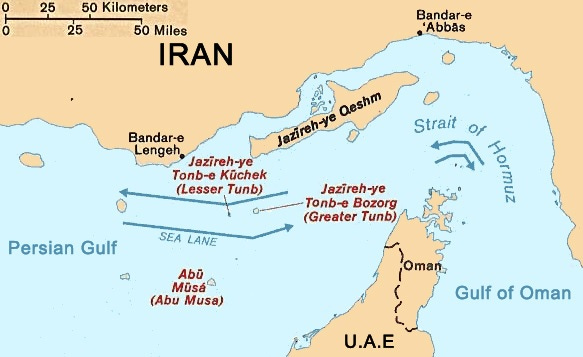

For example, Russia recently issued a joint statement with the GCC that challenged Iran’s claim over three disputed islands in the Persian Gulf. Iran regards these islands as an inseparable part of its territory and has refused to negotiate or arbitrate over them. Many Iranians felt betrayed by Russia’s position on the islands, as their government has portrayed Russia as a strategic partner and ally against US pressure and sanctions.

The three disputed Persian Gulf islands

Similarly, China issued a joint statement with Saudi Arabia in December 2022 that called for a peaceful resolution of the islands dispute. China has also been reluctant to invest in Iran’s economy or buy its oil at full capacity, despite pursuing a 25-year strategic partnership agreement with Iran.

In this context, Salehi in his recent interview called for Iran to have more balanced relations with all the Great Powers, meaning Russia, China, and the US. And he called for dialogue with the US to improve Iran’s ties with its longtime enemy. He argued that such “balanced” relations would give Iran more options, more leverage, and more benefits from each partner. He criticized the current situation of Iran being too reliant on China and Russia.

Many within the Islamic Republic’s foreign policy establishment increasingly say it has swayed from its founding principle of “Neither East nor West,” which meant staying independent of both blocs during the Cold War. This principle has been replaced by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s “look to the east” preference in the wake of increasing US pressure in recent years.

Notably, Kharazi, who is a senior advisor to Khamenei on foreign affairs, went even further in his criticism of Russia, saying that Russia should solve its own territorial disputes with Japan over the Kuril Islands through negotiations.

Iran’s Relations with the US: A Vicious Cycle of Hostility

Overall, it is fair to say that Iran wants more respect and reciprocity from Russia and China, and not be a junior or dependent partner. Many in Iran also want a more balanced foreign policy that does not favor one Great Power over another, but there are many obstacles to this.

Perhaps the biggest factor is the US’s apparent reluctance to engage with Iran in a meaningful way and its persistence in its hostile and coercive policies towards Iran. Iran is a scapegoat in US politics and changing this status requires a political price that no US politician is ready to pay, certainly not Joe Biden.

As Peter Beinart recently argued in The New York Times, Biden squandered the opportunity to address the Iran issue and peacefully resolve the nuclear crisis early in his term. He has kept Trump’s sanctions on Iran, which amount to economic warfare against Iran. He has also broken his campaign promise to return to the JCPOA without preconditions, and instead early on in his term demanded more from Iran than what was agreed upon in 2015.

As Beinart observes, this follows a similar pattern as with other countries like Cuba: continued US pressure and inflexibility has pushed them to rival great powers, even when they would prefer to have balanced relations with the US.

What is clear is that Iran is loath to trust the US again after the JCPOA experience and may not believe that constructive relations are even possible. The key question for Iran is whether it can overcome its internal divisions and external pressures and seize the opportunity for a more constructive and balanced relationship with the US. The key question for the US is whether it can overcome its political polarization and ideological biases and adapt to a multipolar world where Iran is a regional power that cannot be ignored or isolated.

For now, it seems that both sides are stuck in a stalemate, with neither willing to make the first move or offer the necessary concessions. As a result, Iran continues to lean on Russia and China for support and survival, while the US continues to rely on sanctions and coercion for leverage and influence.

However, this status quo is unsustainable and unstable, as it risks undermining both sides’ medium to long-term interests, as well as the stability and security of the region and the world.